Ideas + Insights

March 14, 2022Restoring Equity: How Historic Preservation Efforts in Black Communities Seek to Shift the Narrative

In West Baltimore’s Harlem Park neighborhood, the Harlem Theatre, designed in the 1930s as a 1500-seat theater for Black movie-goers, was once known for its elaborate architecture and its heavily illuminated marquee. The building that houses the theater has served as an important cultural and community anchor for more than a century, a fact that activist Angela Francis, who purchased the theater in an attempt to save the historic landmark, knows well. But getting support and funding from organizations to recognize the theater’s significance and support the restoration has not been easy.

“There are certain landmarks that shouldn’t have such a hard time going and applying for grants,” says Francis. “The preservation organizations that would typically be helping people like us are not helping us.”

The challenges of raising interest in and support for the Harlem Theatre aren’t unique, and community activists and organizations focused on African American heritage and history have worked to address the inequities for many years. For most of United States history, decisions around what buildings are important enough to preserve and which ones are torn down, which spaces deserve a place in history and which ones are erased from our collective memory are largely made by white decision-makers.

“Historic places that matter to Black neighborhoods have not always been valued by historic preservation professionals for their association with Black culture,” says Jen Goold, Executive Director of the Neighborhood Design Center (NDC). “It is essential that we uplift and support Black people who are working hard to preserve landmarks like the Harlem Park Theatre. They show us how historic buildings can evolve to share their stories — including the ones that can be hard to hear. They also show us the ways in which access to resources remains inequitable and push to change the system.”

"We want to be there for this community as it turns history into a foundation for a just future."

— Jen Goold, Executive Director of the Neighborhood Design Center

The emphasis on both favoring historic architecture and placing a higher value on the history of white Americans means that Black historic landmarks are often devalued and left out of preservation efforts. However, the marginalization of Black history in the built environment doesn’t just end at the preservation of historic buildings; it also impacts the preservation of culture and whose story ultimately gets told.

“The stories we connect to places can really change our understanding of those places and can either erase or change history,” says NDC’s Community Design Program Director Allie O’Neill. “This is why preservation matters and why so often we have to push at the edges of preservation. How do you legitimize so many things that the historical preservation cannon has left out?”

In this piece, we offer a snapshot of community efforts to preserve Black history in the built environment, not just as an effort to reclaim historic properties, but to reclaim the historic narrative and re-frame our connection to the past and our present understanding of Black history, ultimately impacting how future stories are told, preserved and valued.

Bostwick House: Re-imagining History

Built in 1746, Bostwick House is a historic fixture in the town of Bladensburg, Maryland. Located above the Port of Bladensburg, Bostwick is known by historians for its place in American history, most often for its connection to the famous battle in Bladensburg during the War of 1812 and for its notable residents through the years, including Benjamin Stoddert, the first Secretary of the Navy.

Yet, while most Bladensburg residents are aware of the historic structure’s presence, as Samuel Parker, AICP, former Commissioner of Maryland National Capital Park and Planning Commission, says,“ They don’t know what it is. There’s no connection other than that it’s an old house falling apart on the hill.”

Bostwick’s history in the town, which today is nearly seventy percent Black, is also complex. It has strong ties to the trans-Atlantic slave trade via its builder and Stoddert’s father-in-law, Christopher Lowndes. The building that was home to white figures recognized in U.S. history also housed enslaved Africans who first landed at the Port of Bladensburg and played a role in Black history in the town dating from that time through Reconstruction and into the 20th Century with segregation and Jim Crow.

The Town of Bladensburg, which now owns and operates Bostwick after years of private ownership and neglect allowed the building to fall into disrepair, is tasked with saving and restoring the historic building while re-telling and preserving a history centering Black people that in many ways has not yet been told.

“How, then, do you do that?” says Parker. “You don’t do that by restoring the physical appearance and creating a beautiful place. You have to figure out what the true story is and how it fits in, past, present, and future.”

With that concept in mind, Parker, along with Bladensburg Mayor Takisha James and several community stakeholders came together with NDC to begin imagining a strategy for the preservation of Bostwick House. Over the last year, stakeholders convened to discuss plans for Bostwick’s renovation and re-use. While the group did not come to a final agreement on the direction of the house, they are moving forward with some guiding principles for the restoration.

“It’s not going to be a museum,” says Mayor James. Instead, she envisions working together with the community to prioritize a space that serves the community with the history embedded in its programming.

“If you have programs and activities there, you start to embed the stories of the past. It becomes more than a park with building on it.”

— Bladensburg Mayor Takisha James

While optimistic about the building’s future, both James and Parker note that they are at the very beginning of what will be a lengthy, expensive process. In addition to the amount of money they need to raise to complete the restoration, they also need to make a sustained effort to continue to get buy-in from a rapidly changing community. Today, nearly a quarter of Bladensburg’s residents are not U.S.-born., adding the need to tell the community’s story in a way that resonates universally.

“The biggest challenge to getting here and moving forward is getting more people bought into and caring about the story, and it will not be successful if the story is not told in a holistic way,” says O’Neill. “If the story is picked through and we just talk about the first Secretary of the Navy living in the house and not the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, it will be a missed mark. It’s not acceptable anymore to tell a partial history. Telling stories and welcoming people in a way that will make it feel interesting is the biggest challenge.”

Parker mirrors that sentiment. “That whole story is important to tell because it happened, but it also means something to people that are here today. Even though the cultural traditions may be different, there are commonalities in the struggle. The stories of what has happened to people who lived in Bladensburg, worked in Bostwick, and were enslaved in Bostwick …there are fascinating tales that have to be brought out but all with the purpose of trying to get the community of Bladensburg to see worth in a building that was inhabited by rich white folks.”

In addition to garnering community support, those involved with the restoration must relay their vision to donors and funders to show the value of Bostwick beyond its floors, doors and walls.

“The needle pushes you toward the physical,” says Parker. “That’s what people see and tend to believe that a physical structure was about — the brick, the plaster, the fireplace. You need the physical to tell the rest of the story, but the story is equal to [the physical] and is embedded in the restoration process. That’s the needle we’re trying to move.”

North Brentwood: A Historical Heartbeat

Just two miles northwest of Bladensburg, the Town of North Brentwood stands as a testament to the resilience and self-sufficiency of Black communities. As Prince George’s County’s first incorporated African-American town, North Brentwood has a unique history that the community is actively designing to preserve.

North Brentwood was incorporated in 1924 as a function of the Sundown towns, deliberately all-white cities or neighborhoods that exclude non-whites through discriminatory laws and practices, surrounding it. While physically and economically cut off from the surrounding communities, North Brentwood became its own self-sufficient sanctuary for Black residents.

“This wasn’t the best land,” says Town Manager Jackie Goodall, noting that the land that North Brentwood sits on where Black people were allowed to own property was once known as the Bottoms. “But this was a place they made home and we want to ensure that nobody forgets it.”

Goodall has been involved in “a little bit of everything” as it pertains to preservation efforts in North Brentwood. Among the many projects Goodall is helping to support is the restoration of Sis’s Tavern, which has served as a tavern, grocery store, barber shop and music hall and has been an important community anchor through all of its iterations.

Sis’s began as a juke joint where greats like Pearl Bailey and Duke Ellington would stop after playing gigs in Washington, D.C. that they would have to leave immediately following due to segregation. “Sis’s was one of the first places where Black entertainers that left D.C. could stop,” says Goodall. “There were other places in PG County that they could go, but here they had a white linen restaurant where you could sit down and it was much more exclusive than the sandwich places.”

After serving many different purposes as the heartbeat of North Brentwood, Sis’s closed and was acquired by the town as it was in need of restoration. The community worked with NDC to create a new interior design for Sis’s which will re-open this year as a community event space. The new design pays homage to the tavern’s history while providing a space for North Brentwood’s current and future residents to utilize.

Efforts to preserve history in North Brentwood have gone beyond the restoration of historic buildings to include monument projects like the Barrier, which was once a traffic barrier that served as a physical divide between North Brentwood and the all-white town of Brentwood. The community collaborated with NDC and a team of artists led by artist Nehemiah Dixon to create a monument from the barrier that would acknowledge the structure’s history while re-imagining its purpose in the community today.

“Instead of just removing the barrier and saying ‘everything is okay,’ remembering the time that the communities were separated is important, especially in the time we are in now,” says Goodall.

“History forgotten is doomed to repeat itself.”

— Town Manager Jackie Goodall

Remembering that history in North Brentwood also extends to preserving history where a physical structure no longer exists. The community has received funding to re-purpose a vacant lot on Rhode Island Avenue as a memorial to the entrepreneurs and business people that provided the backbone of North Brentwood’s economy that had to be able to stand on its own due to racism. They are currently working with NDC on a grant which will help develop guidelines for how they want to approach public arts projects and address questions like whether they want to create signage to mark places that may no longer be there.

“Older people know, but in the future, people won’t know that this was a spot where Black kids in PG county went to elementary school because they couldn’t go to the other schools that were all white,” says Goodall.

Imagining the North Brentwood of the future is at the base of why preserving the town’s history is so important right now. “All across the country and the DMV, there are areas that were predominantly Black communities…we’ve had gentrification in a lot of these communities. Once the demographics change, people forget the history. There are a slew of communities that the residents don’t know were once predominately Black. North Brentwood is a hidden jewel. People move here because it’s a place that people can walk up and down the streets. After African American people start moving out or seniors die or sell their homes, the history will be forgotten…We’re ensuring that the history is not forgotten, even as the community changes.”

West Baltimore: Preservation as Activism

The move to preserve Black historical structures can serve as a means to promote Black history while also re-shaping the current state and future of Black neighborhoods. Such is the case in West Baltimore, where restoration efforts are both a way to capture legacy, and to leverage historic spaces for much-needed reinvestment into historically divested communities.

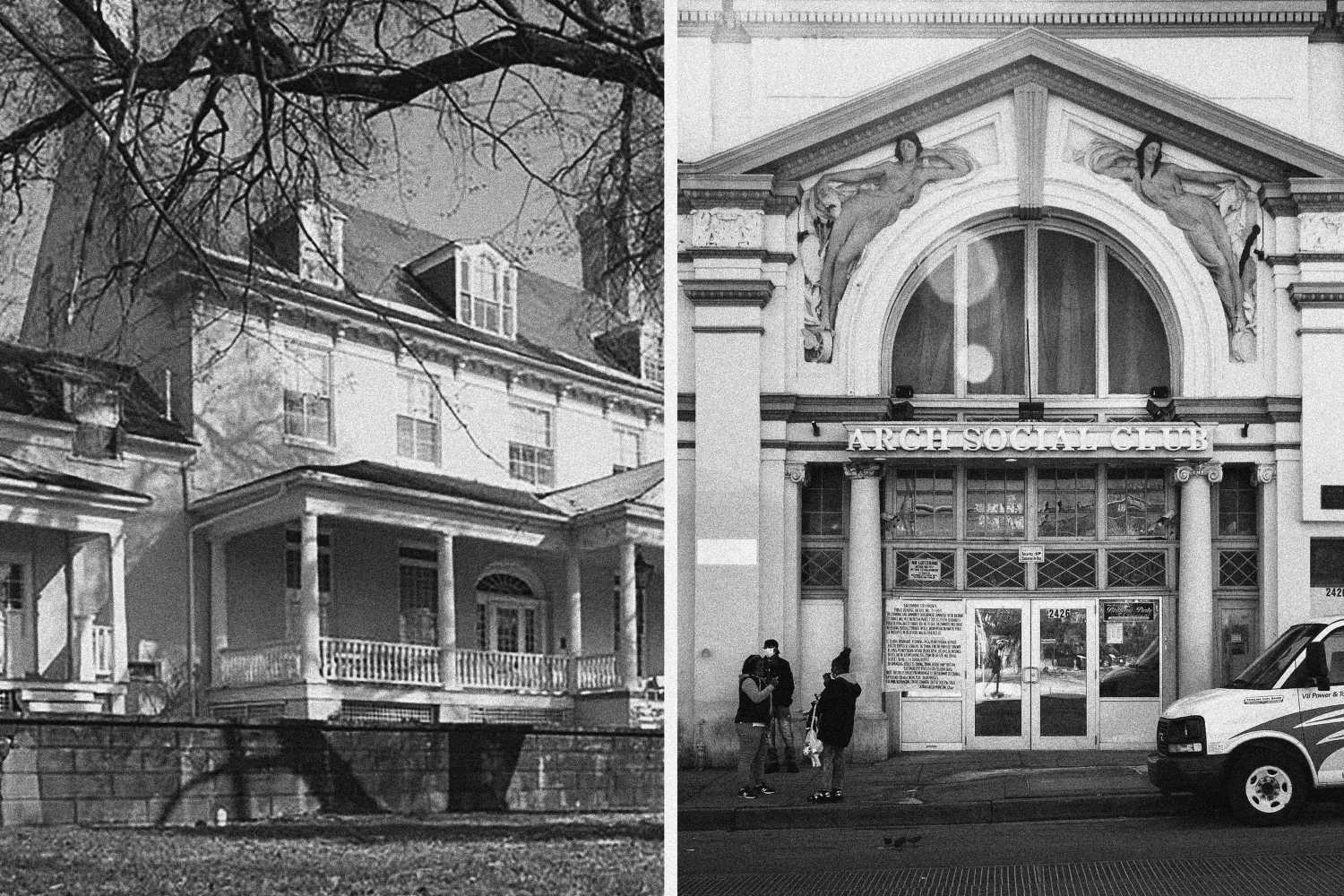

Van Anderson’s introduction to the Arch Social Club on Pennsylvania Avenue began when his father took him there to celebrate his 21st birthday. While he enjoyed the club’s “nice, comfortable atmosphere,” he didn’t understand the significance of the space until more than a decade later, when he learned that the building was not just a nightclub, but that it had been a hub of cultural, social and economic engagement in the community since it opened its doors in 1905.

For more than a decade, Anderson has presided over the club which started as a place where Black men could gather in the highly segregated community and went on to become a space that served a myriad of purposes in the neighborhood; it was a place where musicians could play various types of music that couldn’t be played in church; it was a spot where the Black community could “socialize in peace”; it was a center for people to share ideas as it stood through different eras and discuss topics from prohibition to Marcus Garvey.

"In good times, it’s a place where we have shows and parties. In times of crisis, like Freddie Gray, or even the situation right now with Covid, we become a social center for coordinating activities to resolve it."

— Van Anderson, President of Arch Social Club

In 2018, Arch Social Club received a grant to make major renovations, including restoring the building’s facade and installing a movie marquee. The funding marked the beginning of a fundraising effort to support ongoing building renovations to include upgraded restrooms, and plans for making the building ADA compliant, installing a full-size, heavy duty elevator, incorporating solar energy, and more.

Anderson sees the restoration as not just an effort to help preserve the club’s legacy, but as a way to position the Pennsylvania Avenue corridor as a Black arts district that the Arch Social Club is a part of. “I am envisioning it beyond just cultural engagement,” says Anderson. “I view it as a possibility for being able to kick off a Black main street, not just an arts and entertainment district, but something similar to Rosewood and other economic hubs.

Part of that “main street” vision also includes the Cab Calloway houses, which were once owned by the late jazz legend. Calloway’s daughter donated the Pennsylvania Avenue properties to the club (another Cab Calloway property on Druid Hill avenue was demolished). The two houses need to be gutted and renovated, after which plans will be to create a community cultural convening space with a small Cab Calloway museum.

“We want to attract tourism,” says Anderson, who knows that doing so will take a significant, collaborative community effort as a history of crime, poverty and drug use in the community has landed it on a list of “places not to go” in Baltimore. “The Arch social club views Penn North as critical to the development of North Avenue, rising to developing West Baltimore. We only view ourselves as a hub, but after it’s developed, the floodgates will open. Canton started with just a hub and a section, but look at it now.”

Most important to the restoration of both the Arch Social Club and the Pennsylvania Avenue Corridor, however, is that the revitalization reflect the needs of the community supporting it.

“We don’t want people to feel like we’re coming in like Big Brother to ram ideas down people’s throats,” says Anderson. “We don’t want outside developers to come in and tell us what to do in the area. We don’t want to build houses along the strip; we want black businesses to provide all the things our people consume. We want to define what we want to do.”

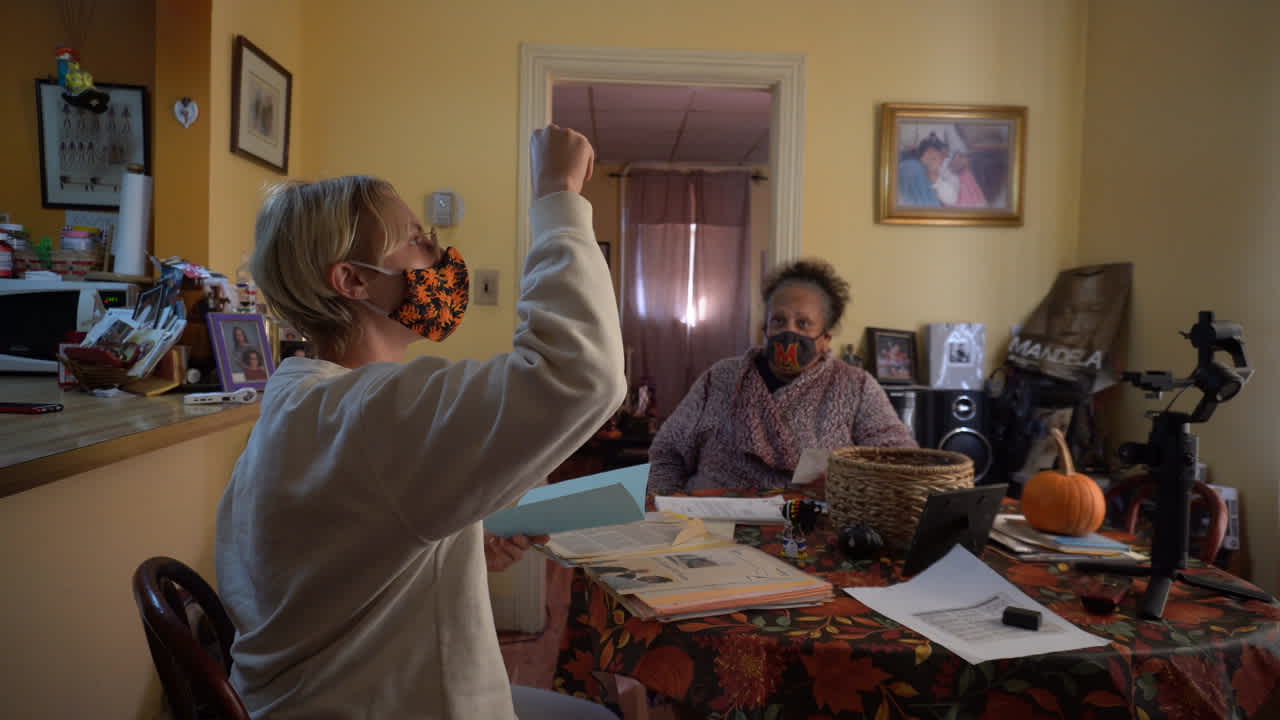

For Angela Francis and her son and fellow activist Tony Francis in Harlem Park, the effort to save the Harlem Theatre isn’t just about preserving a building and its history, but ensuring their community’s future.

“It wasn’t about the building,” Angela Francis says of her efforts to save the theater. “It was about the entire community, but the building stands as an important community landmark, so it became the anchor.”

Both Angela and Tony Francis have been residents of Harlem Park and have firsthand experience with both the benefits and challenges of living in the neighborhood. Lack of access to resources including fresh groceries, high levels of crime, and blighted buildings are among the challenges that Harlem Park residents regularly face due to the historic divestment in their neighborhood. “I live right across the street from a school that’s in the news everyday,” says Tony Francis.

Angela Francis was launched into activism when her own Harlem Park home was selected by the City for demolition. Since that time, she, now joined by her son, has fought diligently for the revitalization of the community and against the displacement of Harlem Park residents. “It wasn’t enough to just own our home or ten homes,” says Angela Francis. “We had to come up with a revitalization plan for our own community.”

It was this plan, in part, that drove her interest in saving the Harlem Theatre. With the entire block in danger of being demolished or put into receivership, restoring the theater became a way to stave off demolition plans, preserve the theater’s history, and breathe new life into the community. The Harlem Theatre is now an anchor for a future cultural arts village center, and the activists are in the process of raising funds to restore the building for that purpose.

Angela Francis points to several factors in the slow warm-up to interest in the restoration project from funders and other organizations. “It’s them not understanding our value, period. The value of us as human beings, our intellectual value, and our historical value,” Angela Francis says. “Our activism stems from the fact that regardless of the murder rate, we are people who still care.”

“It’s our calling, and if we don’t do it, then no one else will,” says Tony Francis. “This community has too much history, especially Black history, to let it go the way of Harlem and Atlanta. We would like to see our kids have ownership in a thriving community…We’re tired of seeing Black people being convinced to move out before the amenities can come.”

Angela Francis looks forward to the redevelopment of the theater, which she refers to as a “treasure chest” and “teaching museum” of Harlem Park. However, she knows the theater is just one part of the history and legacy that will benefit the community’s future residents.

“The journey is more important than the buildings,” says Angela Francis. “We’re creating a guide to fight.”

Restoring Equity Resources

Our work is rooted in challenging the historic disinvestment discussed in this article by supporting the growth of healthy, equitable neighborhoods through community-engaged design and planning services. If you would like to learn more about how NDC can work with you and help support efforts to restore equity in your community, please take a look at the services we offer. Please contact us with any questions or to talk about how NDC can collaborate with you.

NDC Services that align with Restoring Equity are (1) Arts Planning and Cultural Programming and (2) Architectural and Interior Design.

Architectural and Interior Design

In collaboration with you and a team of stakeholders, we identify a vision for your space, produce design options that reflect what we’ve heard, and deliver design documents that you can use to fundraise, apply for grants, or further develop designs with a licensed design professional.

Code Analysis

Site Planning

Conceptual Building and Space Plans (Existing Buildings and New Construction)

Arts Space Technical Assistance Program

Interior Design and Furniture Plans

Facade Improvement Programs (Design and Management)

Visualizations

Project Management

See Examples

Arts Planning and Cultural Programming

Our placemaking team listens to the unique history of each neighborhood and proposes design and art solutions that anchor and amplify those stories in place. We can support you in identifying public art opportunities, artist selection, designing placemaking elements and events, or securing a historic designation for your building or neighborhood.

Public Art and Administration (Includes Artist Residency Programs, Management of Artist RFQs and RFPs)

Public Art Implementation

Placekeeping and Placemaking

Historic Preservation

Place-based Identity

Public Space Design

Cultural and Public Artplans

See Examples

Organizations and Funders

Our projects with NDC’s community partners are supported by organizations and grants dedicated to restoring equity and preserving history. The following organizations, funders and resources can be utilized as a guide to connect you to the financial and other additional support you need.