Ideas + Insights

April 5, 2023Fostering a Culture of Care and Maintenance in the Built Environment

Bringing the issues into focus

The onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and the resulting demands on public spaces placed a spotlight on the need for continued care and maintenance of these spaces, highlighting historical inequities and bringing the question of who is ultimately responsible for caring for public spaces and how to manage this maintenance in an equitable way into focus. The resulting dialogue has centered on the need for a cultural shift in the way that municipalities and designers work with community residents and the value placed on long-term care and maintenance.

“Inequality is being designed into the city, every day.”

— Justin Garrett Moore, Designer and Urbanist

“...Inequality is being designed into the city, every day. It’s not something that happened 100 years ago, or 50 years ago…In a very different way, we do it every day by designing this imbalance into our city.” Justin Garrett Moore, transdisciplinary designer, urbanist, and former head of the Public Design Commission for the City of New York, shared these sentiments in the Urban Omnibus article, Care, Where. His call to develop a “Department of Care,” a city department responsible for maintaining and caring for public spaces in one of the world’s largest cities, brings the conversation around a culture of care and maintenance in the built environment to the forefront.

But while the Covid-19 pandemic highlighted the need for interventions, in Baltimore, the needs of the Covid era are only at the tip of the iceberg in many neighborhoods dealing with public health and safety issues brought on from a long history of lack of care, maintenance and investment on both a municipal and commercial level. The disinvestment in these communities has led to a deep disparity in the quality of the local built environment.

The resulting issues range from crumbling sidewalk infrastructure making it difficult for children, the elderly or those with physical limitations to walk, to thousands of city-owned vacant lots, which, unmaintained, attract dumping, pollution and infestation into these neighborhoods.

Hazards like rusted sharp metal fencing poking out of sidewalks, broken glass on playgrounds and lead and asbestos left to disseminate into the environment as old buildings crumble in place are widespread in historically divested communities, but rarely seen in the city’s more affluent neighborhoods. These hazards are the very visible, physical symptoms of structural, racialized disinvestment that also influences public health outcomes for a community’s residents ranging from shorter life expectancy, higher asthma rates, heat island effect, higher pedestrian mortality, and much more.

“A lot of times in places with small budgets like Baltimore, we rely on neighborhood groups to do things like care for vacant land...”

— Neighborhood Design Center Executive Director Jennifer Goold

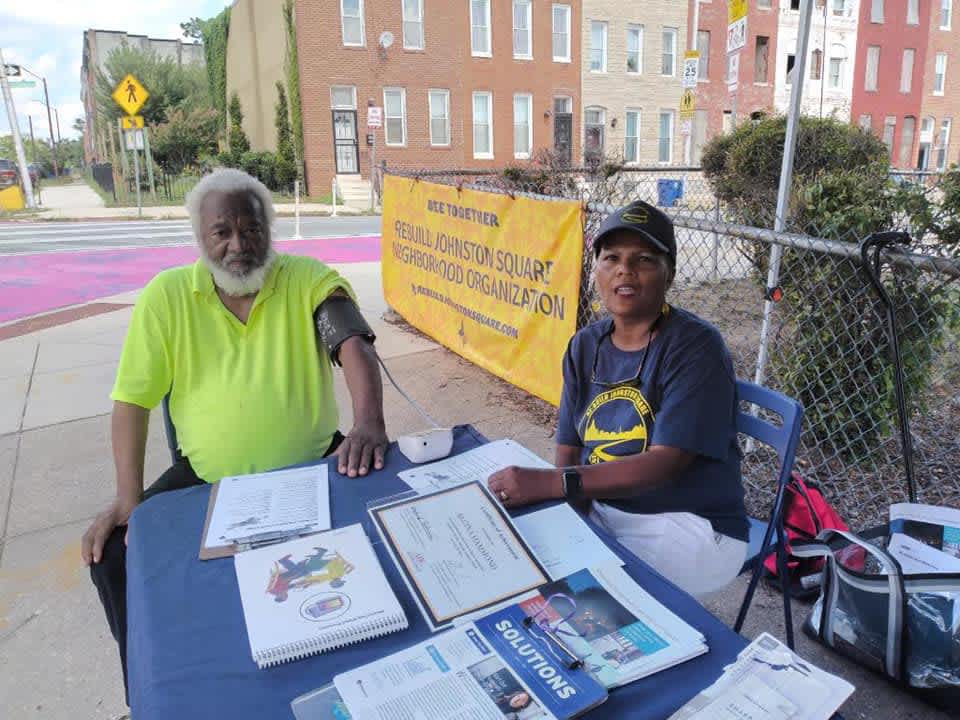

Taking matters into their own hands: transforming the Johnston Square neighborhood

Finding that no one seemed to be taking responsibility for the public realm in Baltimore’s Johnston Square neighborhood, Regina Hammond took matters into her own hands. Back in 2013, the now founder and Executive Director of ReBuild Johnston Square, became fed up with the neglect and lack of care from the City in her community. Along with her husband Keith, Regina began working to organize her neighbors to help revitalize many of the long-neglected spaces in their area.

“I didn't want to look at empty lots with mattresses thrown on them, and the kids didn't have anywhere to play,” Regina said. “We had a park, it was a local neighborhood city park but it was a mess, it was a dumping ground. It was overgrown and it was completely neglected, so we hosted a week-long clean-up in the neighborhood and included that park. That was really our first big attempt at turning this community around.”

Since that time, she has worked non-stop to improve the Johnston Square neighborhood. In 2017, after the Johnston Square Community had invested many years of volunteer hours in keeping the park clean while continuing to call the City to task for their lack of care and maintenance of the park, the City Department of Parks and Rec secured a $1.5 million grant from the National Recreation and Park Association to renovate the park, now known as Henrietta Lacks Educational Park. See how the Neighborhood Design Center supported this project.

In addition, Johnston Square has transformed seven formerly vacant lots into gardens, and maintain 30 lots total throughout the neighborhood. The maintenance of these renovated spaces falls to a community-organized group she refers to as the Green Team, made up primarily up of a small group of the neighborhood’s retirees.

“The Green Team actually works on a schedule like clockwork,” says Regina, “So you won’t see waist-high grass on any lots that we’re responsible for.”

And while Regina is proud of the work that her community has done and continues to do to maintain their public spaces, the question of why the onus of both bringing the resources and caring for those spaces has fallen so heavily on individual community members when in other areas, municipal support seems to be the expectation is never far from her mind.

“I'm either going to sit still and look at that junk because I can't get DPW to come out and pick it up, or I'm just going to do it myself.”

— Regina Hammond, founder and Executive Director of ReBuild Johnston Square

“It is a fact of life,” Regina says. “So I’m either going to sit still and look at that junk because I can’t get DPW to come out and pick it up, or I’m just going to do it myself...We have a voice now. Eventually, somebody’s going to see that there’s something really unfair about certain neighborhoods and how they are treated compared to other neighborhoods. But until then, I’m not going to live in garbage. We’re going to clean it up. Because everybody’s got an issue—they’re short-staffed, there’s not enough money—these are all the excuses we hear.”

In August, Mayor Brandon Scott announced a Clean Corps Initiative to help clean and maintain historically disinvested public spaces in Baltimore, representing a step in the right direction when it comes to fostering a culture of care and maintenance in the city. Read more about it here.

“Poor communities are having to operate as an unfunded Department of Care for the City of Baltimore,” says NDC’s Jennifer Goold. “Right now the system is being bandaged on the free labor of the residents. Certainly residents have a role to play, but that should be equally balanced. It should be uplifted by the residents. It shouldn’t be on their backs at the level of care and maintenance.”

The devaluing of care and maintenance has long roots that stem everywhere from the historic undervaluing of the work of women in domestic spaces to devaluing the work of people of color throughout history. Impact is often measured in terms of new investment, but the maintenance and “maintainers” of those projects take a backseat and fly under the radar. “People love new, and they love big ideas, but maintenance really matters,” says Jennifer. “Respect needs to be given to the maintainers, because their work not only improves people’s mood and safety, it is also hands-on work that reconnects people…it’s so important and meaningful, but historically devalued and undervalued through systems of oppression.”

Maintenance is paramount for tree planting initiatives

The areas in which this devaluing takes place are broad, and extend well beyond buildings and parks. The urban tree canopy is a space that may not traditionally be thought of in the realm of disinvestment and care and maintenance, but benefits greatly from an understanding of a culture of care.

NDC is the lead consultant on the Right Tree, Right Place program through the Prince George’s County Department of Public Works. Jason Sprouls, NDC Community Forestry Program Manager, helps lead the program which seeks to establish broad maintenance of the tree canopy in Prince George’s County.

Trees offer tremendous benefits, both to the environment and the humans living in that environment. They capture air pollutants and cool the atmosphere, improving a neighborhood’s air quality which in turn improves the health of its residents. They reduce the amount of water erosion and improve stormwater runoff by soaking up water in their roots. The benefits also go beyond the environmental. They transform a community’s streetscapes, have been shown to improve mental health, and have even provided traffic calming benefits.

Historically disinvested neighborhoods, due to both lack of initial investment and lack of tree maintenance, tend to have less tree canopy than more affluent neighborhoods, meaning residents receive fewer health and environmental benefits from trees.

Increasing the tree canopy in these neighborhoods helps to increase those benefits, but while planting new trees receives the most attention, the maintenance is what ensures those benefits will continue for the long term.

“I would contend that maintenance is arguably the most important step in any tree planting initiatives in neighborhoods that have been historically underserved.”

— Jason Sprouls, NDC Community Forestry Program Manager

This is because for all of the great benefits of trees, without a solid plan for maintenance in place, these trees can also become a challenge for those in a community if they are not maintained. Throughout their life span, roots can damage sidewalks, they can infiltrate storm and sewer pipes below ground or their limbs can break off and damage someone’s car.

The resulting effect in neighborhoods where trees have historically not been maintained by the local government and where those municipalities have been slow to fix issues through maintenance or removal, is that community members have more negative experiences associated with trees. While the benefits may ultimately outweigh the negative aspects, the lack of positive experiences with trees may cause residents to view them as a liability. “People are more distrustful when we lead with so many great benefits of trees, but we’re not the ones who are left with servicing the trees.”

In addition to the general neglect and lack of care and maintenance from municipalities in low-income neighborhoods proving to be a hurdle in improving the tree canopy, the history of how these projects have been traditionally maintained also provides a challenge. For more than 50 years in the urban forestry industry, many of the tree canopy models have been developed to cater to affluent white neighborhoods. These neighborhoods are often quick to adopt a volunteer-based maintenance model often because of more available leisure time and personal resources for the project. But this model is not appropriate in every neighborhood.

“I think it’s really prohibitive and unfair to expect people in underserved areas to shoulder the burden of maintaining projects that were installed in their neighborhood, especially when you consider that people in those neighborhoods usually have longer working hours,” says Jason. “My number one goal as the program manager for this is never expecting it to be volunteer-led. I never want to force a neighborhood group to shoulder the responsibility of taking care of county-owned trees. I think the way you can change people’s hearts and minds is by showing that the stewardship and care is going to be there from the beginning.”

Capital and maintenance are often two completely separate parts of municipal budgets

“There’s a long-standing conversation about the fact that a lot of funding and investment is for initial capital investment into a place and that capital and maintenance are often two completely separate parts of municipal budgets,” says Jennifer.

She continues: “The group that will be responsible for installing a highway or installing a public park is not the same group that will be responsible for caring for it in the future, and they don’t even usually have to be certain that there is a budget for caring for it in the long term. Sometimes you’ll see city investments happen and then the maintenance is not upheld. Maintenance in general is not uplifted as being valuable, and important work. People get really excited about the big change, but they don’t necessarily spend a lot of time on resources or give a lot of props to the maintainers in the world.”

And when those maintainers aren’t supported or considered, causing public spaces to fall into disrepair, instead of examining the factors and inequity that often lead to the neglect, it is instead projected as a moral failure of the residents of the communities in which the conditions exist.

“Communities with vacant buildings are called ‘blighted,’ which is a disease-based word,” says Jennifer. “Those are moral judgments that are being baked into something that should be neutral information.”

NDC Program Director Allie O’Neill underlines the need to push back against the tendency to shift blame and responsibility for a lack of care and maintenance onto those living in historically divested communities and to place moral judgments on community members. She opens the conversation into the larger issue of trauma that the lack of care has caused and the resulting effects on both the mental and physical health of the community. She stresses a need to consider the full context surrounding why these issues exist in order to address them effectively.

“What message does it send about who we care for and who we value and who we don't, as a society?”

— Allie O’Neill, NDC Program Director

“It’s applying a holistic perspective to understand what is behind the things that are happening. We need to deepen our understanding and look at invisible forces at play. What effects does it have on people to grow up in places with maintained parks versus unmaintained parks? What message does it send about who we care for and who we value and who we don’t, as a society?”

For Jennifer, understanding these forces at play and beginning to embed this culture of care into our city and society comes down in many ways to a shift in focus of what is valued. “There are many psychological and cultural components to uplifting the culture of care and the culture of maintenance. In our discussion of what matters about doing community investment and community development work, we could really flip what it means to live in a healthy city on putting a lot more value on maintenance and care than we put on creating new things...Maintenance needs a closer link to new investment and clear pathways that are linked within municipal systems. There needs to be a revolution in re-valuing and evaluating care.”

The Neighborhood Design Center offers services that align with a Culture of Care.

department

Landscape Design and Environmental Resilience Planning

Well-designed public landscapes and gardens provide meaningful community spaces, mental restoration, and room for reflection and healing. We work across scales and specialize in participatory planning — because great designs are informed by and for the community.

Community Landscape Design

Schoolyards and Learning Environments

Green Infrastructure Design and Planning

Community Forestry

Multimodal Transportation and Pedestrian Planning

department

Architecture and Community Planning

The Architecture and Community Planning team at the Neighborhood Design Center specializes in participatory architectural design, place-based arts initiatives, and planning. Our team of architects, designers, planners, and engagement specialists hold strong commitments to design excellence, social justice, and responsive plans that prioritize community power and increased local self-determination.

Engagement and Facilitation

Community Planning

Architectural and Interior Design

Arts Planning and Cultural Programming

More Information

Quick Links

Organizations and Funders

Web Resources and Connected Issues

Washington Post: Baltimore transit equity study spotlights racial disparities around neighborhoods

Baltimore City: Equity Analysis of Baltimore City’s Capital Improvement Plan, FY2014-FY 2020

OECD.org: Unpaid Care Work: The missing link in the analysis of gender gaps in labour outcomes

The Hill: The roots of our child care crisis are in the legacy of slavery

AmericanProgress.org: Maternal Mortality and the Devaluation of Black Motherhood

IAPHS.org: 400 Years of Chains: The Over-policing of Black Bodies and the Devaluing of Black Pain

The Groundwork Collaborative: The Nation’s Moment of Truth: America’s legacy of devaluing care